Why Input Validation and Output Encoding Matter

Injection attacks (SQLi, XSS, command injection, LDAP/XML injection, etc.) remain some of the most damaging and common vulnerabilities, consistently represented in OWASP Top 10 risk categories. In almost every case, the root cause is a missing or misapplied combination of input validation and output encoding.

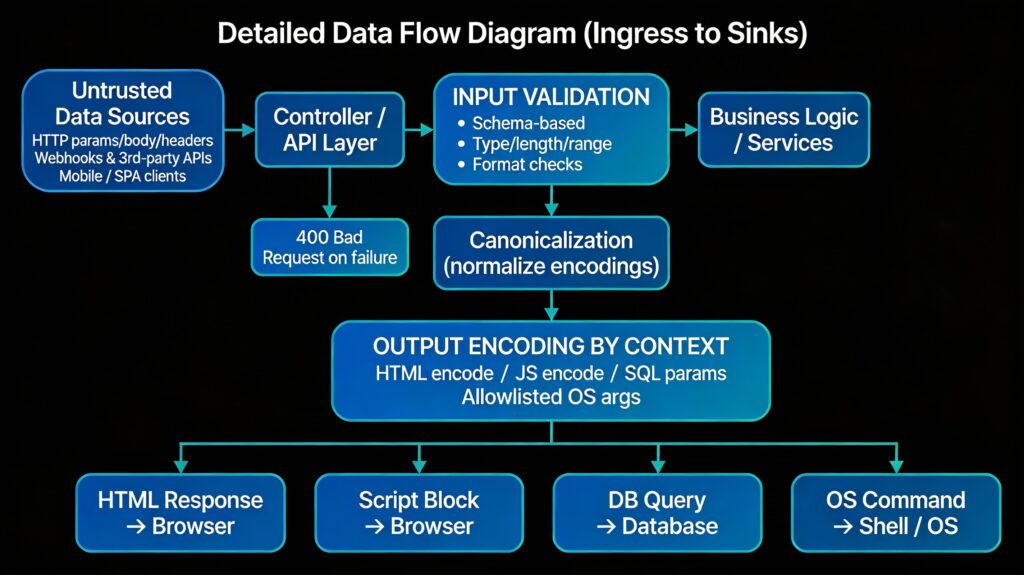

For Niyava-like architectures – API-first backends, dashboards, admin consoles, and integrations – untrusted data flows in from everywhere: HTTP parameters, JSON bodies, headers, message queues, third-party webhooks, and internal services. Treating all such data as hostile until validated and encoded is a foundational secure coding habit.

Core Concepts: Trust Boundaries and Sinks

To reason clearly about input validation and encoding, it helps to identify two things in your system:

- Trust boundaries: Places where data crosses from a less trusted domain to a more trusted one (for example: public internet → API gateway; external partner → integration service; frontend → backend).

- Sinks: Sensitive operations where malformed or malicious data can cause harm: SQL queries, HTML rendering, JavaScript execution, OS commands, file system access, LDAP/NoSQL queries, etc.

Secure coding principle:

- Validate at trust boundaries (as early as possible).

- Encode at sinks (as close as possible to where the data is used).

In this model, malicious payloads should be rejected at validation or neutralized by encoding before they reach any sink.

Input Validation: Design Principles

OWASP emphasizes that all client-provided data must be validated before use—this includes URL parameters, form fields, JSON bodies, cookies, and headers. Niyava teams can standardize on these principles:

- Allowlist, not blocklist

- Validate by type, length, range, and format

- Canonicalize before validating

- Centralize validation logic

- Fail closed

- Any validation failure should result in immediate rejection (e.g., HTTP 400) with a generic error message.

- Do not “auto-correct” or silently truncate security-sensitive fields.

Example (pseudo Node.js-style):

// Example: Express + validation middleware conceptually

app.post('/users/:id', validate({

params: { id: 'uuid' },

body: {

email: { type: 'email', maxLength: 254 },

name: { type: 'string', minLength: 1, maxLength: 100 },

age: { type: 'integer', min: 13, max: 120 }

}

}), (req, res) => {

// If we reached here, all data has passed strict validation.

});

Libraries and frameworks in most ecosystems offer equivalent constructs, making it realistic to standardize this pattern across Niyava services.

Output Encoding: Context Matters

Validation alone cannot protect against all injection vectors, especially when dealing with rich text, complex search queries, or dynamic content. Output encoding ensures that even if untrusted data is present, it is rendered as data and not code.

Key rule: encode for the exact context where data is used.

| Context / Sink | Encoding Strategy | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HTML body | HTML entity encoding | Escapes <, >, &, ", ' so payloads render as text. |

| HTML attributes | Attribute encoding + quoted attributes | Prevents breaking out of attributes (", ') and injecting handlers. |

JavaScript in <script> or inline | JavaScript string encoding | Escape quotes, newlines, backslashes, closing tags. |

| URLs / query strings | Percent-encoding | Use dedicated functions (e.g., encodeURIComponent). |

| SQL queries | Parameterized queries / bound parameters | Strongly preferred over manual escaping. |

| NoSQL / search queries | Structured API with parameters, not string concat | Avoid building query strings with untrusted input. |

| OS commands | Avoid direct commands; if unavoidable, strict allowlists per argument | Pass arguments as an array to APIs that do not invoke a shell when possible. |

Examples of what not to do:

// XSS-prone

res.send("<div>" + req.body.comment + "</div>");

// SQLi-prone

const sql = "SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = " + req.query.id;

db.query(sql);

Improved patterns:

// Safer template with auto-escaping (for HTML body)

res.render('comment', { comment: req.body.comment });

// Parametrized SQL

const sql = "SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?";

db.query(sql, [req.query.id]);

These examples rely on libraries and ORMs that provide context-aware encoding and binding.

How Input Validation and Encoding Reduce Risk

OWASP data and industry reports consistently attribute a large share of severe incidents to injection vulnerabilities, many of which could be prevented by validating inputs and encoding outputs according to guidelines. Conceptually:

- Input validation blocks malformed or obviously malicious payloads at the edge.

- Output encoding neutralizes content that passes validation but could still be interpreted as code.

For Niyava-scale deployments, adopting both systematically:

- Reduces noise in WAF signatures and reduces the burden on API gateways and firewalls.

- Simplifies security reviews – reviewers check that schemas and context-specific encoding calls are present rather than hunting for every string concatenation.

- Provides a clear mapping from OWASP Secure Coding Practices categories 1 (Input Validation) and 2 (Output Encoding).

SDLC Integration: Making It Routine at Niyava

To make these practices stick:

- Design phase

- Implementation phase

- Use shared validation modules and encoding helpers.

- Mandate parameterized queries and safe templating engines.

- Code review

- Add specific questions: “Are all external inputs validated?” and “Is all untrusted data correctly encoded at sinks?”

- Flag any raw concatenation into SQL, HTML, JavaScript, or shell strings.

- Testing & automation

This discipline forms the base of Niyava’s secure development culture and sets the stage for upcoming posts on authentication, session management, and access control.