Introduction: Why Niyava Cares about Secure Coding

Every feature shipped today is exposed to an internet where attackers constantly probe APIs, mobile backends, and web frontends for weaknesses. Vulnerabilities like injection, broken access control, and cryptographic failures remain dominant in OWASP Top 10 lists, and they almost always trace back to coding and design decisions – not exotic zero-days.

From Niyava’s perspective, secure coding is not a “security team responsibility”; it is a core engineering competence. Addressing security during implementation and design is significantly cheaper than remediation in production and avoids reputational and regulatory damage. This series aims to give teams a common vocabulary, a set of reusable patterns, and a roadmap they can embed into everyday development.

What Is Secure Coding in Practice?

Secure coding is the discipline of writing and reviewing code so that security controls are baked into the architecture and implementation rather than patched on after incidents. It connects three layers:

- Principles: least privilege, fail-safe defaults, defense-in-depth, secure by default.

- Coding patterns: input validation, output encoding, parameterized queries, safe cryptographic APIs, secure configurations.

- Process: threat modeling, code reviews with security criteria, automated scanning and testing across the SDLC.

Standards such as OWASP Secure Coding Practices, CERT Secure Coding Standards, and NIST SSDF provide high-level frameworks. This Niyava series translates those into concise, implementation-focused guidance for product teams building distributed systems, APIs, and microservices.

How This Series Is Structured

OWASP’s secure coding checklist organizes practices into 14 key areas such as input validation, authentication, access control, cryptographic practices, error handling, data protection, configuration, database and file security, and memory management. This series mirrors those domains and overlays them onto modern engineering workflows (API-first, cloud-native, DevSecOps).

| Topic | Primary focus |

|---|---|

| Overview & TOC | Why secure coding matters, how to use this series |

| Input Validation & Output Encoding | Defending trust boundaries and sinks from injection |

| Authentication & Password Management | Hardening identity, login, and password storage |

| Session Management | Cookie and token security, rotation, and logout |

| Authorization & Access Control | Preventing broken access control, BOLA, and IDOR |

| Cryptographic Practices | TLS, encryption, key management, and safe crypto APIs |

| Error Handling & Logging | Failing securely while preserving observability |

| Data Protection & Secrets Management | Sensitive data lifecycle and secret handling |

| Communication Security | Secure HTTP, API, and service-to-service communication |

| Secure Configuration & Hardening | Secure defaults and configuration-as-code |

| Database & File Security | Safe database queries and file handling |

| Memory & Resource Management | Memory safety and resource exhaustion defenses |

| Secure SDLC & Testing | SAST, DAST, SCA, and secure code reviews |

| Governance & Developer Enablement | Sustaining secure coding via standards and culture |

This structure lets teams pick an area that aligns with current incidents or security findings and deep-dive into relevant practices.

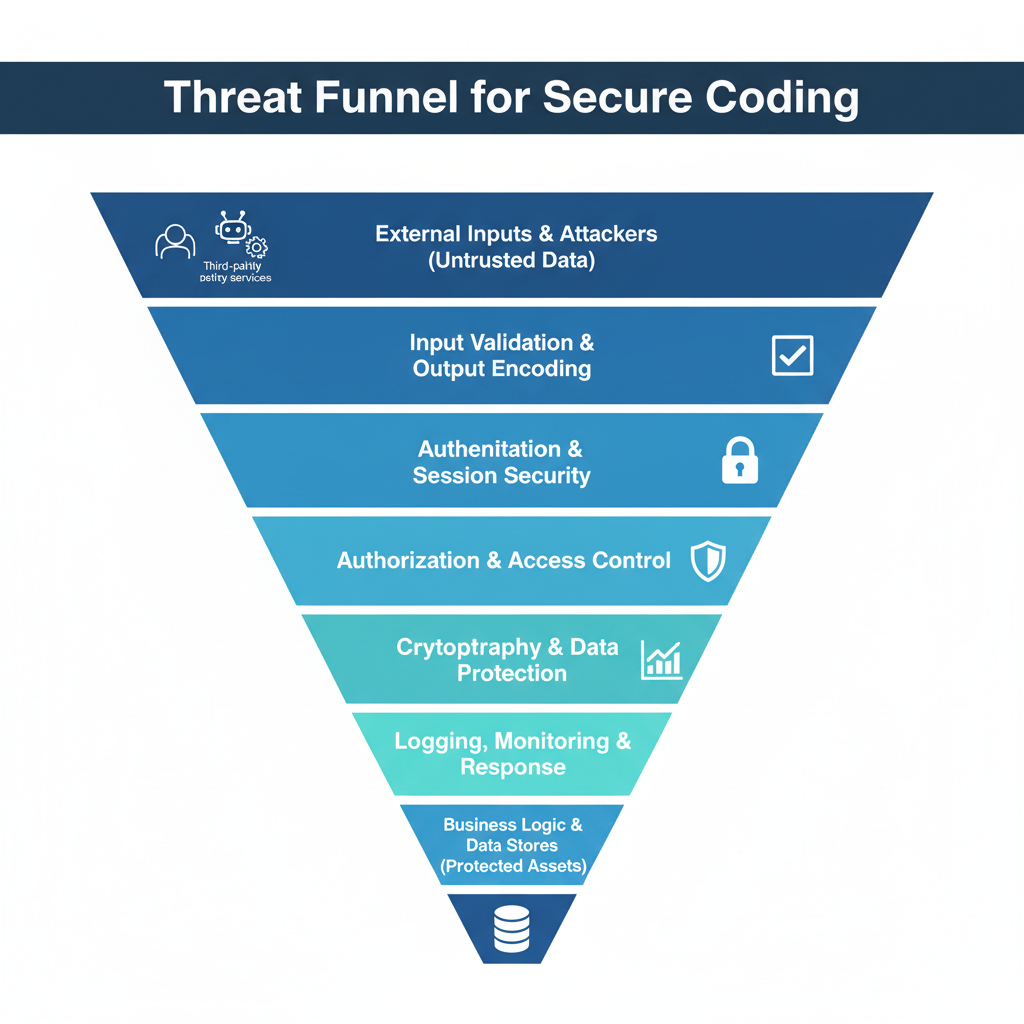

Threat Funnel Diagram (Defense-in-Depth View)

Below is the funnel diagram suggested earlier, expanded with Niyava’s lens of “control layers” that stop or contain attacks before they reach sensitive data or core business logic.

Each band represents a set of secure coding practices that reduce the probability and impact of a successful attack. For Niyava-scale systems, these layers also map cleanly to architecture components (API gateways, auth services, microservices, databases, and observability stack).

How Engineering Teams Can Use This Series

This series is designed as a practical reference rather than a theoretical textbook:

- For developers: Concrete patterns, code snippets, and review checklists to apply in feature work and refactors.

- For tech leads/architects: Diagrams, principles, and control placement recommendations to shape architecture and design reviews.

- For security and platform teams: A baseline of expectations for product teams and a shared language for findings and remediation.

Suggested adoption approach:

- Pick one area per sprint (for example, “input validation everywhere in top 10 APIs”).

- Add explicit secure coding items to definition-of-done templates (e.g., “all external inputs validated against schema, all outputs encoded per sink”).

- Map this series to internal standards or external baselines such as OWASP ASVS or NIST SSDF.

The next post (Blog 2) dives deep into Input Validation & Output Encoding, which form the first and most important layer in the threat funnel.